Regional inequalities worsen as post-Brexit funds fail to match EU

For all the talk of “levelling up” regional inequality in the UK is becoming more pronounced.

If the Conservative Party fight the next general election on delivering their “levelling up” agenda, then they are surely set to lose it. Despite all the discussion around this idea, including the publication of Michael Gove’s white paper in February this year, the policies have entirely failed to match the promise.

Last week, it emerged that government funding for deprived areas and regions through the Shared Prosperity Fund would not match the old EU funding of £1.5bn a year it is replacing until 2025. According to the think tank, IPPR North, this is equivalent to a 43% cut on the average received from the EU between 2014 and 2020. This breaks the Conservative manifesto commitment to, at the very least, match the EU money.

Tackling regional inequality is, however, about much more than specific funds for deprived areas. After all, it should be remembered that it has worsened over decades despite access to EU funds. Fundamentally, it is about the overall macroeconomic model and the extent to which it both redistributes wealth and incentivises economic activity across the whole UK. For decades, the UK’s priorities have been set by the wealthy in London and the South East.

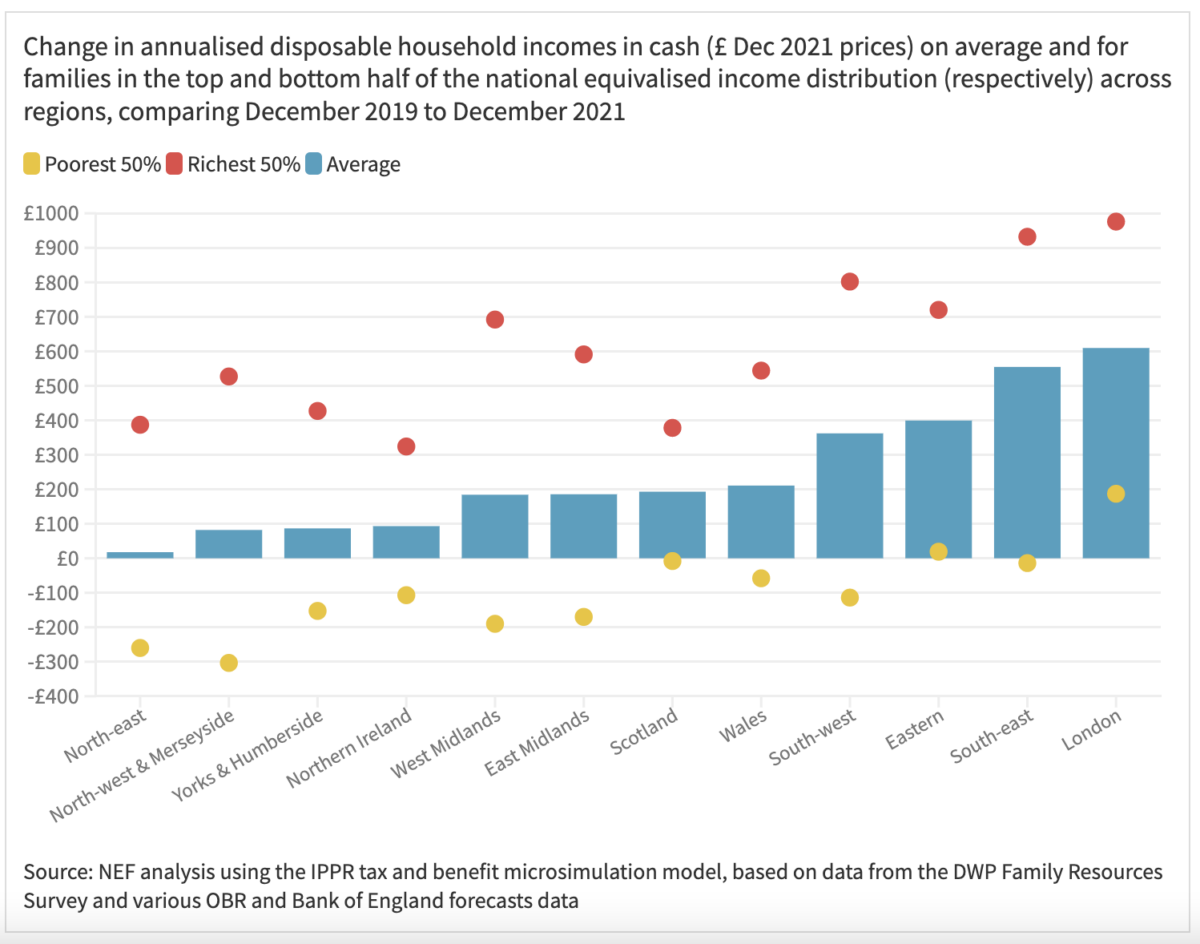

As Andrew Pendleton has argued on Brexit Spotlight, individual income inequality is one of the biggest factors driving geographical inequality between areas. But here, too, the government is entirely failing to deliver – and, in fact, the situation is actually getting worse. Between December 2019 and December 2021, there were striking differences between incomes of those at the median level of the income distribution in different UK regions.

In a blog for New Economics Foundation, Alfie Stirling and Dominik Caddick drew out this dramatic growth in regional inequality: “On average, disposable real incomes have barely risen in the north-east at all since December 2019 (less than £20 per year, or less than 0.1%). Similarly, the north-west and Merseyside (£80, 0.2%), Yorkshire and the Humber (£90, 0.3%) and Northern Ireland (also £90, 0.3%) have barely fared better. At the same time, disposable real incomes in London have increased by more than £600 per year (1.3%) and by more than £550 in the south-east (1.1%).” We reproduce their data in Figure 1. It reflects how white collar professional workers, which were spending less on a day-to-day level through the lockdown period, accumulated large savings. This fed into regional inequality, exacerbating it further, due to the uneven geographical distribution of these workers across the UK.

Figure 1: The gap in income across regions has widened since the 2019 general election

It is not good enough for the Conservative Party, though, to simply blame COVID-19. Their policies have done nothing to address these inequalities proactively. Despite all the talk of levelling up, their response is fiscally timid and makes little political sense from their own point of view, as many Conservative voters are left to struggle on.

This total failure, which will only get worse with the unfolding cost of living crisis, might go some way to explaining how the Conservatives are doubling down on “culture war” issues. The so-called operation “red meat” to save Boris Johnson following the partygate scandal is now playing out. Its latest measure is the outrageously racist proposal to systematically deport to Rwanda asylum seekers and migrants that arrive by irregular routes.

So, the outlines of the next election are coming into view. As the UK faces a cost of living crisis, exacerbated by, not remedied with, Brexit, the Tories will double down on racism and authoritarianism to avoid scrutiny on their record.

April 20, 2022

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.