The politics of the Spring Statement are illogical for the post-Brexit Conservative Party

In a guest post for Brexit Spotlight, Andrew Pendleton looks at the flawed politics of Tory non-interventionism.

Aside from its obvious failings, Rishi Sunak’s spring statement, roundly criticised from both opposition benches and government-friendly media outlets, is politically naïve and tone deaf. Like George Osborne’s infamous 2012 “omnishambles” budget, in which he tried to introduce a higher rate of VAT on some takeaway hot foods, such as pasties and pies, but was forced to U-turn, Sunak’s budget will surely not hold.

It’s hardly surprising there’s a strong aroma of burning tyres in the air as Sunak’s bandwagon, which has been rolling since he wheeled out the largely successful job retention scheme during the first lockdown, comes to a screeching halt. The Resolution Foundation argued that Sunak’s mix of proposed tax changes, which are more generous for better off households than for the poorest, would leave an additional 1.3 million households to fall into absolute poverty, including half a million children.

The main problem households face is that wages are not rising at anywhere near the same rate as inflation, which is being driven by a post pandemic mismatch between supply and demand, especially in commodities, and exacerbated by the impact on oil and gas prices of Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine. Incomes are on course to be lower in real terms than they were in December 2019, which would make this the worst Parliament on record for living standards.

In the short term, the usual macroeconomic levers, such as the Bank of England’s decision to increase interest rates, are unlikely to make much difference to prices and may add further to economic pain, a point on which progressive economists and the British Chambers of Commerce are agreed. Consequently, many expected even the fiscally Conservative Sunak to step in with more support for those now reportedly only asking for food from foodbanks that can be consumed cold because they cannot afford to cook. But he did not.

The politics of letting the cost of living crisis rip

It is, of course, morally reprehensible to leave households – already suffering almost two decades of stagnation in their incomes – to fend off pandemic and Brexit related price hikes alone, or with welfare payments that were not enough to live on even before inflation kicked in. But it is also politically inexplicable for two reasons.

The first is that an overwhelming majority of people in the UK are concerned about rising costs, to the extent that, prior to the Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, almost three-quarters supported price controls on household essentials, including food. And while Sunak’s tax changes will ease the pain for some households, typical working age households will be more than £1,000 worse off in the 2022/23 financial year.

The second is that many of those worst affected will be living in the places at which the levelling-up agenda – arguably the signature policy of the Johnson government – is primarily aimed. There are two ways to look at this and both tell a similar story.

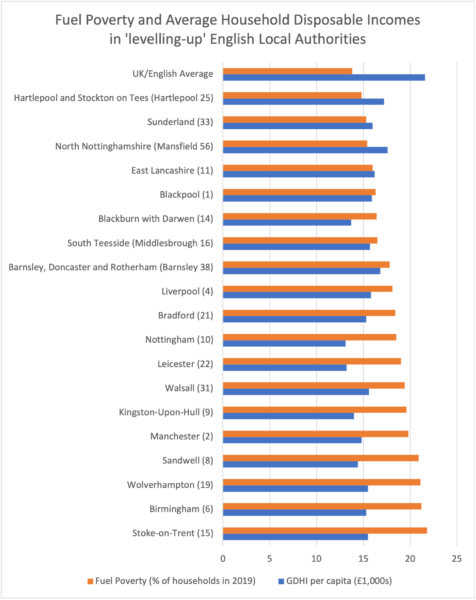

The first is shown in Figure 1. Many of the English local authority areas in the north and midlands that are most often associated with the levelling-up agenda are the most exposed to the costs of living crisis. This is unsurprising as they typically have fuel poverty[1] rates that are above average, household disposable incomes that are below average and are among the country’s most deprived places.

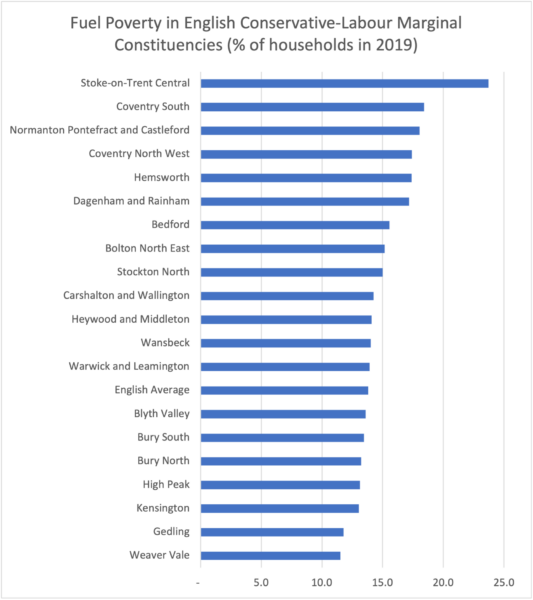

The second is shown in Figure 2. In 12 out of the 20 most marginal Conservative-Labour English constituencies, fuel poverty levels are at, or above, the national average and in all 20 more than one-in-ten households are classed as fuel poor. While some of these areas are not as exposed to the cost of living crisis as the levelling up group of areas, many households will be among those whose living standards are set to fall significantly despite the changes made in Sunak’s Spring Statement.

Ten of these English constituencies are still held by Labour and are likely to be high on the list of those the Conservatives would aim to gain in the next election. Ten were won by the Conservatives at the last election with the smallest of margins. These include Stoke-on-Trent central – won by a margin of 670 votes – in which almost one-quarter of households are fuel poor. But they also include places such as Coventry North West, held by Labour in 2019 by the narrowest of margins and in which, while fuel poverty is below the national average, disposable household incomes are as low as Stoke. Households are highly vulnerable to shifts in costs of living.

The Chancellor’s proposed package of immediate measures – primarily his fuel duty cut and the raising of the personal allowance threshold for National Insurance – was met with a mixture of surprise and anger for its lack of support for those households, highlighted in the graphs above, who face the most significant impacts from rising prices.

He needs to do more for those who will otherwise bear the brunt of this great rupture in living standards because it is the right and necessary thing to do. But it’s hard to see how the Conservatives can make further gains in “red wall” seats, sustain those they’ve already made, or deliver anything meaningful on levelling up unless Sunak has a rapid rethink.

Andrew Pendleton researches and writes on social, economic and environment strategy and policy. He was previously deputy CEO and director of policy at the New Economics Foundation, and formerly also at IPPR, as associate director for climate and energy, and Friends of the Earth, as head of campaigns.

[1] Fuel poor households are those with low incomes, high fuel costs and high energy consumption (affected by the efficiency of their homes) and is defined by households who spend a high proportion of their income on energy bills.

March 30, 2022

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.