Defra versus Department of Trade in the battle for the future of UK agriculture?

The policies of two major UK government departments are working against one another. We take a look at the muddled thinking casting a long shadow over the UK countryside.

This week farmers in England will receive their first payments under the post-Brexit system for agricultural subsidies. In Scotland and Wales, the old subsidy system – based on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) – has been rolled over, with new arrangements only set to be introduced by 2024 and 2025, respectively.

Under the EU system direct payments, which calculate grants on the basis of the amount of land made available to farming, made up 80% of the UK agricultural subsidy budget – with the remainder linked to rural development.

For Brexit’s critics this is an unusual policy area for the simple reason that there is actually very little support for the European status quo from campaigners and progressives – and lots of support for a new approach.

The CAP has long been criticised for subsidising landowners, disproportionately benefiting larger farms over smallholders, and failing to prioritise environmental goals. While the EU claim to be addressing these issues in its latest reforms, campaigners have argued that they do not go anywhere near far enough.

A new agenda for sustainable farming?

So, for once, the UK government are not entirely wrong. Replacing the CAP with a new system of farm subsidies based on environmental and conservation goals could deliver sustainability improvements in agriculture, protecting our countryside and ensuring a just climate transition. But only if it forms part of a holistic, progressive agenda.

Under the new system the UK/English government are introducing, farmers will receive payments that are linked to the protection of six public goods: (1) air quality; (2) water quality; (3) plants and wildlife; (4) preventing environmental hazards and risks; (5) mitigation and adaption to climate change; (6) and conserving the heritage and beauty of the natural environment. However, farmers are already expecting to see a loss in income – with subsidies getting tapered, even though not all farms are participating in the pilot conservation scheme. Given that persuading big supermarkets to raise prices to mitigate a loss of subsidies is likely to be tough, farmers calculate they will be worse off by 2024 – when direct payments are reduced by up to 70%, before ending completely in 2027.

Whether the new system delivers for the environment remains to be seen. But some have given the approach modest support. Peter Hemmings, a dairy farmer who is part of the conservation-based subsidy pilot, told The Times, “From what I can see, I don’t think the new scheme will make up for what I am losing financially. But it’s kinder to nature and is, to be honest, a nicer way to farm – perhaps a bit more like how my father used to do things.”

On the other hand, there is a problem in relying heavily on financial incentives to protect the environment. The RSPB has warned that with some estimating only 70% of farms will sign up to the new sustainability farming framework, this will risk the environmental health of 70,000 miles of hedgerows that are vital for the protection of ecosystems. This could be avoided by legally mandating many of these new sustainability changes, i.e., enforcing them on all English farms, rather than relying on the use of economic incentives through the provision of grants.

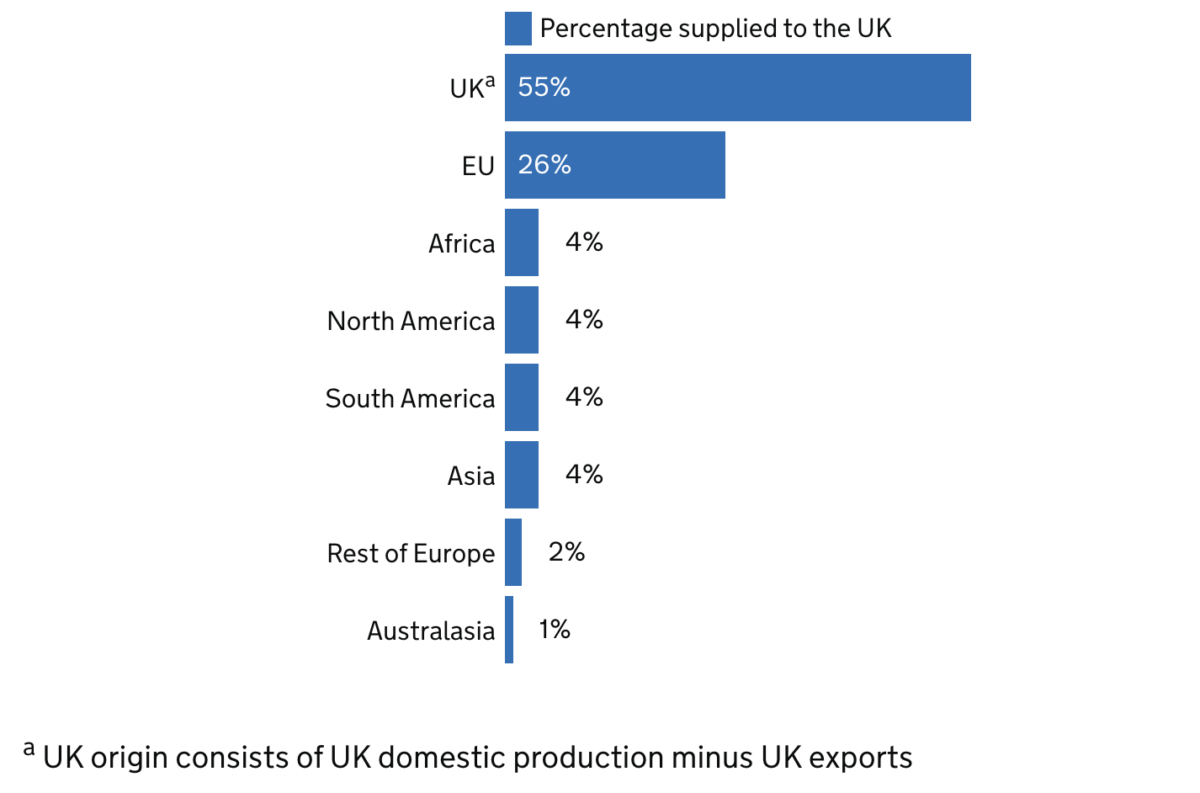

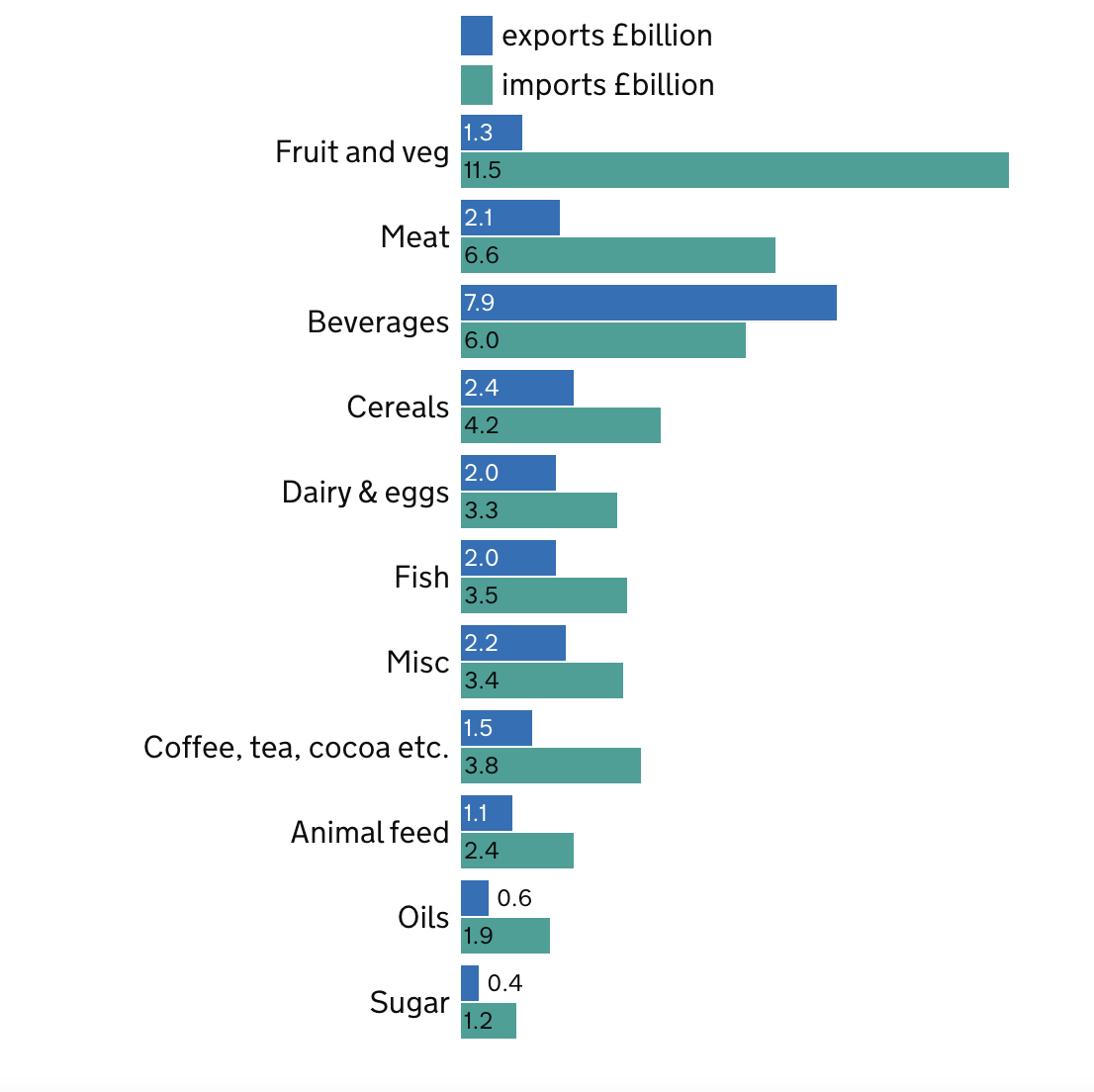

There is a further big problem with the UK government approach. Even before changes to domestic farming that will make it more sustainable, but, potentially, less productive in terms of output per acre of land farmed, the UK was already dependent on imports. As we can see from Graph 1, in 2019, while 55% of food consumed in the UK was domestic in origin, the remainder came from the rest of the world, particularly the EU. And, as we can see from Graph 2, the UK has a particularly large trade deficit in fruit and vegetables and a smaller one in most foodstuffs.

Graph 1: Origins of UK food consumed in 2019

Graph 2: UK food imports/exports in 2019

Where is farming going? It depends what member of the UK government you ask

From an environmental perspective, domestic production, while naturally not always possible for some products, is clearly favourable to depending on food being shipped from overseas. There is also some hope that new technology could assist the green transition, providing a means to increase domestic production without damaging the environment. For example, highly efficient LED lighting systems have been introduced by the Yeovil-based farming company, Global Berry, and offer an ecologically sustainable way to raise yields by up to 50%. Lab grown food also has a transformative potential, but will require careful planning to ensure a just transition for rural areas.

Joined-up politics and regulation would be needed to nurture these developments in a positive direction. For example, the campaign organisation, Sustain – the Alliance for Better Food and Farming, has argued that the government could use public procurement to back farm-focused local supply chains. This would mean that the £2bn the UK state spends on food each year supports ecological sustainability and social goals in agriculture.

But in contradiction to such sensible, progressive measures, the trade policy pursued by the government runs directly counter to its stated environmental goals. The Australia trade deal, for example, would open up the UK market to industrial farming products, shipped with a huge carbon footprint from the other side of the world, potentially flooding the UK market with low quality, environmentally damaging food, undermining local produce.

This would create the absurd situation of allowing high carbon, industrial foodstuffs into the UK market at the point when the domestic agricultural system is being nudged in a more sustainable, low-intensive direction.

What’s more, the government’s entire trade agenda seems to be fixed on corporate goals – prioritising open markets at all cost, and without any of the social and environmental mitigations that exist in the common, European market, which they have, of course, chosen to leave.

This will be a particular source of anger for the governments of Wales and Scotland. It means that even though they have significant powers over their domestic agriculture, they have no say in the trade policy that the UK government pursues. So, any changes they make domestically could be swiftly undermined by these deregulatory deals.

Defra ministers are well aware of these issues – and stalwart Conservative supporters, like the Mail newspapers, have been campaigning against the trade agenda. Earlier this year an ‘absolutely furious row’ was reported between the two secretaries of state – with Liz Truss’ Department of Trade allegedly enjoying the upper hand over George Eustice at Defra. But with rural areas a bedrock of Conservative support, we have surely not heard the last of it.

November 30, 2021

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.