COP26: Replacing EU trade with global will bring huge environmental costs

The turn away from Europe shows the contradictions of the ‘Global Britain’ narrative.

At the COP26 summit in Glasgow the government is keen to furnish its credentials as a world leader in environmental policy, and are presenting this as part of their post-Brexit “Global Britain” vision.

Trade has always been an important element of this “global” Brexit agenda. Many Conservative MPs associate the EU with social and environmental regulation (“burdensome red tape”) and want to use leaving as an opportunity to sign new, lighter touch agreements, which use trade policy as a vehicle to quietly dump these protections.

The government follows this “benefits of Brexit” argument and have been seeking new trade deals. They are finalising agreements with Australia and New Zealand, and have applied to join the “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership” (TPP), which brings together a bloc of countries around the Pacific rim.

The content of these deals are often unfriendly to the goals of environmental protection through regulation. But it also raises an even more obvious problem for their argument at COP26: making up for lost EU trade by doing more with countries much further away will massively increase the environmental costs arising from the trade.

The campaign group, Best for Britain, have crunched the numbers – and predictably seen this borne out in the projected data. They found that replacing the fall in EU trade seen in the first quarter of 2021 (when trade in UK-EU goods fell 23%) with non-European trade would put an additional 6.5m tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere due to the increase in shipping miles. This is a level equivalent to about 44,000 transatlantic flights.

As Professor Paul Ekins, Director of the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources argues, “It’s quite simple, the farther you need to move goods, other things being equal, the more emissions you create and so increasing our carbon footprint is pretty much baked into increasing trade with countries like Australia over countries in Europe.”

Another example of a contradictory set of policy goals?

Fortunately, the government may well find that in practice it is simply impossible to replace lost EU trade with the growth of non-EU markets. Trade is already very strongly based on location and geography with tariffs and regulations a secondary factor in the scale and value of goods flowing across borders.

The UK’s own analysis of its deal with New Zealand found that the (small) benefits of economic growth would flow entirely to the other side – a remarkable failure of negotiation given that the UK was the larger party in the talks. Even so, China will remain New Zealand’s key trading relationship, accounting for some 30% of exports.

What’s more, the era of ever rising volumes of global trade is coming to a close. Tellingly, although they provided much of the initial diplomatic push, the United States is no longer part of TPP. Despite their huge ideological differences, both the Trump and Biden administrations have backed an industrial policy based on ‘onshoring’, which incentivises supply chains to return to the home market, rather than prioritising greater trade liberalisation (although Trump’s nationalist version of this approach was inconsistent, and strongly prioritised corporate interests, despite claiming to stand up for American workers).

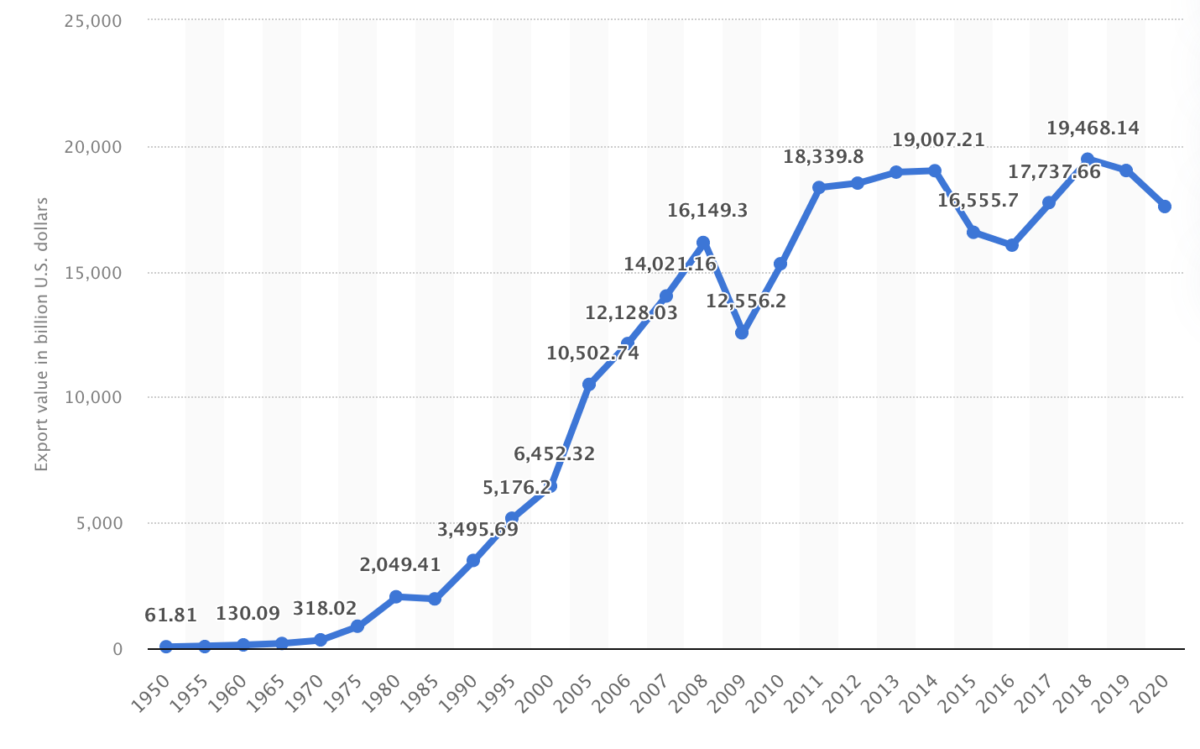

This move in the US is part of a broader pattern. The last decade has seen global exports stagnating – bringing to an end the relentless growth seen across the post-WW2 period (see Graph 1). With supply chain vulnerabilities being exposed in the fallout from COVID-19, this isn’t likely to change anytime soon. In fact, climate shocks mean that the pattern is very likely to continue in the decades ahead.

An analysis by the management consultancy firm, McKinsey, found that extreme weather events caused by climate change will significantly increase the risk of supply chain crises in the decades ahead, further incentivising onshoring (where it’s possible). They estimated that the risk of hurricanes hitting semiconductor supplies would rise by 2 to 4 times by 2040; and, similarly, they expect ‘rare earth’ mineral extraction (materials critical in electronic equipment and renewable energy production) to see a 2 to 3 times increased risk from extreme rainfall by 2030.

Producing more locally makes sense as both a prevention and adaptation strategy for climate change. Reducing food and product miles is one of the most straightforward ways to achieve a direct impact on CO2 emissions. At the same time, offsetting climate vulnerabilities in global supply chains means prioritising local production.

So, this is another area where the government’s policy lacks coherence. As we’ve argued before, Brexit is an exercise in economic nationalism that runs against any credible sense of self-interest and offers a subjectively pro-business policy that lacks the support of most businesses. The pursuit of an outdated trade liberalisation agenda, and in defiance of the government’s stated climate goals, is part of this wider pattern of muddled policy making.

November 2, 2021

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.