Back to the single market? Pressure grows for new deal

Dave Levy looks at the whirlwind of factors heating up Britain’s Brexit debate.

There is a growing realisation that the Tories’ hard Brexit isn’t working. It has led to a reduction in trade (£), both imports and exports, failing businesses, a falling currency, and a labour shortage crippling various industries (but especially agriculture and hospitality). Inflation is now running at 11%. We have weaker growth, expected to flatline next year, reduced foreign inward investment and falling domestic investment. Added to this, is the withdrawal of the EU’s regional development and social fund expenditure, which, despite the government’s “levelling up” promises, it has failed to match. In short, the economy is not in a good state and Brexit has made a bad situation worse.

Meanwhile, the government is heading to a conflict with the EU over the Northern Ireland Protocol that will only add fuel to the fire, risking EU retaliatory action and breaking the UK’s commitments in international law.

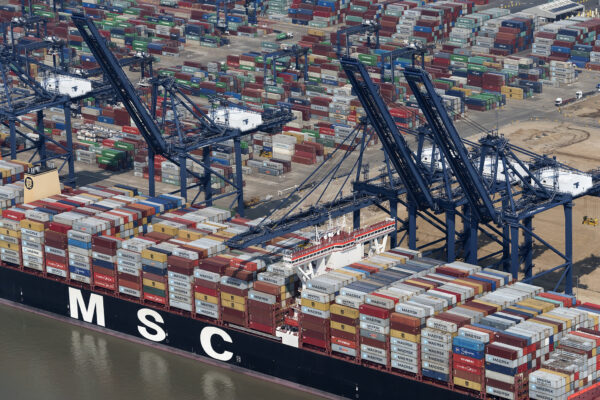

One of the biggest problems for the economy, apart from the labour shortage, is the new friction on the borders between Great Britain and the European single market.

The simplest answer to this would be to re-join the customs union and single market. Politicians still tend to recoil at this idea, fearing the backlash of Brexit voters and mindful of the legacy left behind by Britain’s 2019 “Brexit election”. But has the single market pendulum of popular opinion started to swing back in favour of single market membership? Tobias Ellwood MP, a Tory, has called openly for the UK to re-join the single market and even arch Brexiter Daniel Hannan mused recently that we would have been better off staying in the single market.

At my union conference, I successfully moved a motion that committed the GMB to seek improvements to our Brexit deal. Labour MP Anna McMorrin was rebuked by the Labour higher-ups for calling for a single market arrangement for the UK. Her colleague Stella Creasy has argued that Labour’s silence on the Brexit deal leaves it unable to challenge the Tory narrative. Labour’s weakness on the topic is compounded by the decision of leader Keir Starmer to whip Labour to vote for the Brexit deal ,which is now causing so many problems for our economy.

The general public may be further ahead of the curve than the politicians, too. Polling company Redfield Wilton report that a majority of voters would vote to re-join the EU, though the 57%/43% split illustrates a still divided country. They also showed that voters are sanguine about the prospects – only 31% think that the EU would support the UK re-joining, and 50% think it’s unlikely the UK will apply to re-join in the next decade.

Keir Starmer’s disappointing Brexit intervention

Having let David Lammy, and to some extent Rachel Reeves trial a new Brexit line, Kier Starmer recently broke his silence, delivering a speech with a “five point plan”. Starmer insisted that a Labour government would not seek to re-join the EU’s single market or customs union or reintroduce freedom of movement — let alone seek to reverse the 2016 Leave vote. His alternative plan is important, but leaves glaring holes.

Does Labour propose to put the yet-to-be-implemented import checks on EU goods in their reformed agreement? Will it try and ease the Labour shortage by allowing workers from Europe to return more easily? Why would the EU agree to freedom of movement for the professionally qualified only? Asking for mutual recognition of qualifications to allow professional services firms to operate more easily in Europe without recognising that we need workers in agriculture, logistics, hospitality and even the NHS seems to be Labour’s self-defeating version of Boris Johnson’s infamous “cakeism”. Does any of this help jobs and the environment in the east coast and southern port cities? Why is Horizon Europe, the R&D agreement included in the plan but not Erasmus, the EU’s education programme?

Starmer also talks about agreements on data and financial services – and this is certainly important as the Tories have expressed a desire to diverge from the EU’s orbit in the name of financial innovation. Of course, you would be forgiven for thinking that the 2008 financial crisis would have taught us that we do not want more financial services deregulation. And while the UK currently has a data adequacy arrangements with the EU, there are fears that the new data protection bill may jeopardise this.

Overall, Starmer’s vision is disappointing and the speech itself was often vacuous, lacking substantive detail on a number of these points and showing the usual preference for soundbites over policy.

Above all, he is terrified of setting out a principled case that seeks to lead, not follow, the electorate. Ironically, he risks losing Labour voters – especially young and working-age voters – with this strategy.

Davy Levy is a member of the Another Europe Is Possible National Committee and an activist with the GMB union and the Labour Party.

July 14, 2022

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.