UK manufacturing exports fall sharply. Does it matter?

Probably, yes. But we’re still waiting for some key data.

The UK’s decision to pursue a very hard Brexit has put significant barriers in the way of selling goods to our largest market: the European Union. Consequently, the great majority of economists always anticipated that this would lead to a decline in UK exports – and that any new market access opened up by government trade deals would not be able to offset the decline in EU trade, due to our simple geographical proximity with the European market.

Data is starting to confirm this basic prognosis.

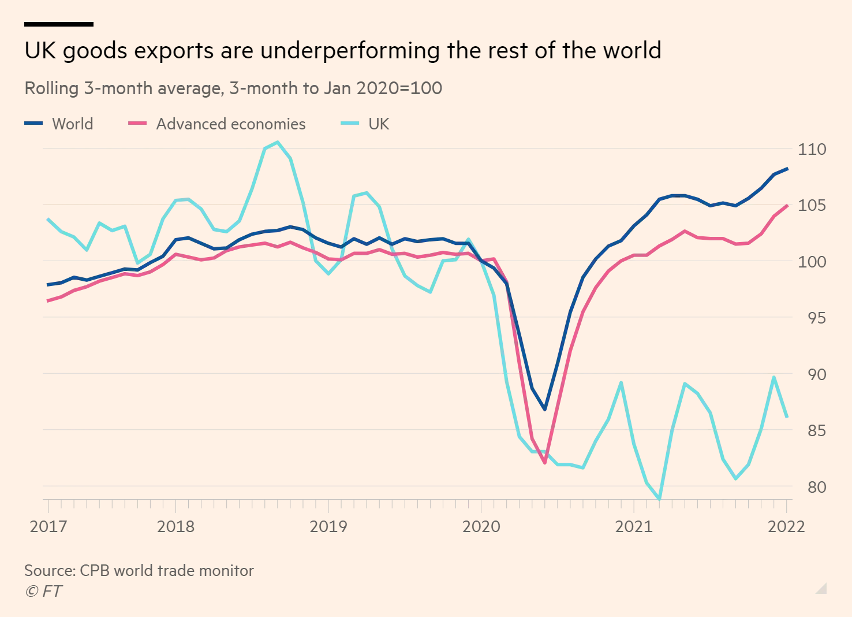

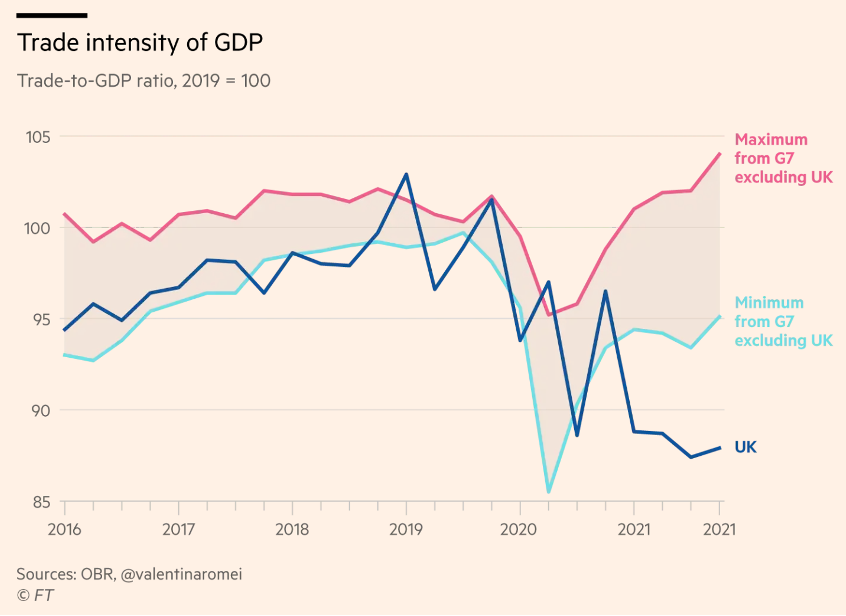

As you can see from these graphs published in the Financial Times last week, the post-COVID recovery of UK exports has lagged behind both the rest of the world and other wealthy economies (Graph 1), while the UK is becoming a less ‘trade intensive’ economy, i.e., trade is now less important to overall economic growth (Graph 2).

So, does it matter?

Manufacturing has a crucial role to play if regional inequality in the UK economy is to be actively addressed and building new sustainable industries is a vital part of the green transition. So, for any 21st century left agenda manufacturing, including investing in new quality, high tech jobs, is going to be really important.

We already have a pretty good basis to argue that UK manufacturers will not make up for lost sales in the European market through new trade deals (that tend to have deregulatory implications for the environment, agriculture, health, procurement and food, which make them unattractive for progressives anyway).

But the question we do not yet have data on is whether import substitution can take place on a large enough scale to make up for lost EU sales. UK manufacturers could make up for falling European sales by selling more to the British market. Because it’s also become more difficult to import to the UK from the EU, there is an incentive for buyers to source more products domestically. This is, broadly, what an ‘import substitution’ policy means.

The key metric to look out for is the total value of UK manufacturers’ product sales. Up till now, this has been falling very sharply due to COVID and Brexit. In 2019, it was £402.2 billion, while in 2020 it was just £358.7 billion.

While we know anecdotally that import substitution is occurring, the question is whether it’s happening on a large enough scale to make up for the loss of European export trade. This seems unlikely, even though there will probably be some rebound from the very low 2020 manufacturing sales data. But we won’t know for sure until the data is out.

Interestingly, the UK government do not talk about import substitution. The language underpinning their economic policy is all about free trade, openness and ‘global Britain’. This stands in stark contrast to the economic reality of increased barriers to EU trade – and is a sign of the incoherence and muddled thinking of Britain’s Brexit vision.

March 28, 2022

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.