The labour shortage crisis in the UK explained: what you need to know

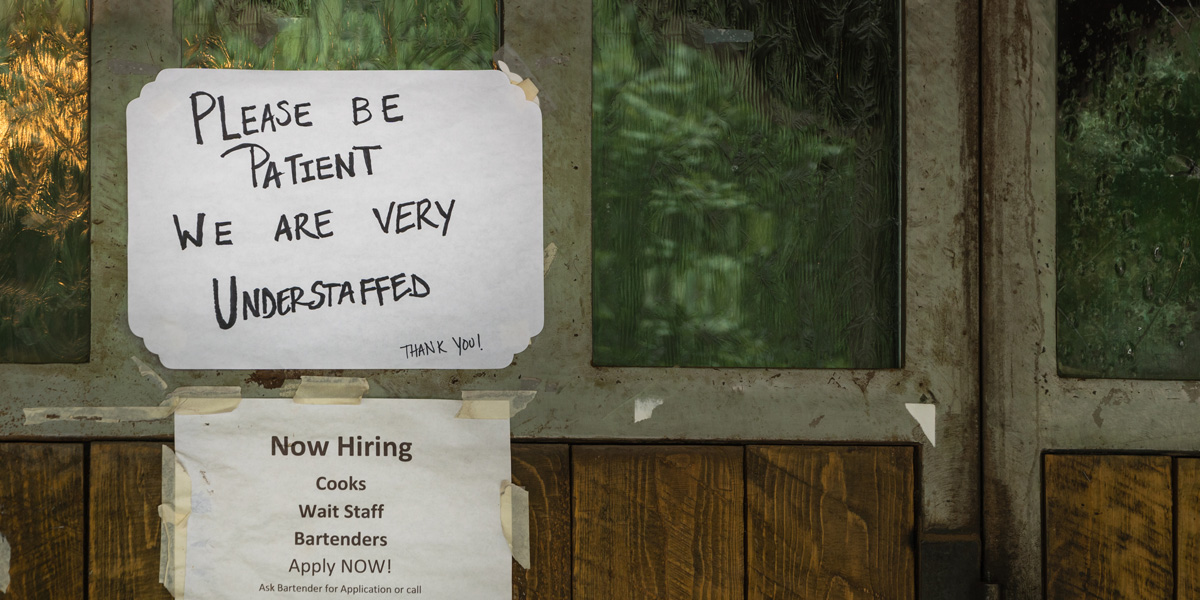

It’s become a familiar sight in the pubs and restaurants of London. Walls are adorned with the same posters: “Experienced staff needed – apply within”. But it’s not just the hospitality sectors that are impacted. Large parts of the economy are facing serious labour shortages.

Ranjit Singh Boparan, whose company, 2 Sisters Food Group, dominates the UK poultry processing sector, warned that the situation was so bad that the UK could face, “the most serious food shortages that this country has seen in over 75 years”.

“The critical labour issue alone means we walk a tightrope every week at the moment. We’re just about coping, but I can see if no support is forthcoming – and urgently – from Government, then shelves will be empty, food waste will rocket simply because it cannot be processed, or delivered, and the shortages we saw last year will be peanuts in comparison to what could come.”

In the hospitality sector, industry bosses estimate that the combination of Coronavirus and Brexit has led them to lose around 1 in 5 workers – often immigrants who have gone back to their countries of origin with no plans to return. As a result, between April and June there were 102,000 vacancies in the sector – an increase of 12.1 per cent since 2019.

A recent academic report on UK agriculture also warned that the sector faces ‘disastrous’ labour shortages. ‘Changes to immigration policy are likely to make the situation worse, particularly in the horticulture, dairy, pigs, eggs, and poultry industries’, they argued.

So what’s going on? We address some of the common questions.

Why are lower paid sectors particularly affected?

Under the new immigration rules workers qualifying for a work visa need to have a job offer for a position earning £25,600 a year or the going rate for the job, whichever is higher.

There are exceptions to this. If a position is on the ‘shortage occupation list’, then the job can pay £20,480 a year but no lower. So, sectors that only pay the minimum wage are mostly excluded (for someone 23 and above working 40 hours per week it is £18,532.80).

In addition, there are also special short-term visas which have a sectoral (not an income) requirement, such as the Domestic Workers Visa or the Seasonal Agricultural Workers visa (which we covered on Brexit Spotlight here). But these schemes are short term and highly problematic. They de facto give an employee no right to change workplace without losing their right to work in the UK – and so essentially green light super exploitative conditions.

Shouldn’t workers just be paid more?

Absolutely. The minimum wage isn’t enough to live on – especially in parts of the country where housing is more expensive. A review of working hours and conditions is also urgently needed – with many people forced to work far too long every week just to makes ends meet. The restaurant trade has for a long-time normalised very exploitative, long hours.

But immigration policy is still a big factor?

Yes. On the one hand, even with much better pay and conditions the labour shortages in some sectors are so large that it simply won’t be enough. Ultimately, the UK has an aging population and requires large net flows of immigrants every year to keep things ticking over.

On the other hand, the new immigration policy isn’t designed to protect the interests of UK workers or maintain high employment standards – in fact, it pushes in the opposite direction. Migrant workers with less secure rights to live and work in the UK are always more vulnerable to super-exploitation. The more workers there are in this situation has a knock-on effect for everyone else, creating a race to the bottom in pay and conditions.

This is doubly the case with the super-exploitative short-term visas like the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Visa. But it’s a general problem of the government’s so-called ‘needs based’ approach, which treats immigrants as economic inputs and not people with rights.

How has the end of freedom of movement impacted all this?

Freedom of movement was distinctive because it’s a rights-based system. This favours better economic outcomes because it prioritises equality between UK and EU workers.

By treating UK and EU workers the same in the labour market, this made it straightforward for people to move to the UK. Workers benefited from equal rights. Employers benefited from not having to negotiate lots of red tape if they wanted to hire an EU worker.

The new visa system combines the worst of both worlds. It puts EU migrants off from coming to the UK by making the process burdensome and bureaucratic, while also sending out the political message that they wouldn’t be welcome if they tried to move here. For employers it also means they have to complete a huge amount of paperwork just to get to the point where they can offer a job to an EU worker. So, although the government is supposedly prioritising business needs, in practice the system doesn’t work for them either.

Freedom of movement also had a positive cultural and societal impact – allowing people to move freely with reasonably protected rights across borders, without having to necessarily commit to trying to live in the UK for a very long period of time. This favoured a type of youthful immigration that became very important to many firms in the hospitality sector.

Is there an alternative?

There’s always an alternative. A simple combination of three policies could make a massive difference to the workers and businesses in these sectors. First, the TUC has long argued for the reintroduction of sectoral bargaining committees. These would establish a minimum floor for pay and conditions across the sector. Negotiated between workers and bosses, they would protect the rights of migrants, as well as UK nationals. Second, an immediate increase in the minimum wage to £10 an hour. Third, the reintroduction of a freedom of movement between the UK and EU – which would also open up the EU labour market to UK citizens, restoring their right to work in 27 different EU countries without applying for a visa.

July 29, 2021

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.