The dangerous allure of ‘Europe first’

In an increasingly zero-sum world, full of intensifying conflicts, the demand to prioritise the protection of ‘us’ over ‘them’ will be difficult for liberals and leftists to resist, writes Luke Cooper. This is the second in a two-part article. Part one can be read here.

Brexit was an exercise in economic nationalism driven by anti-immigration and nativist sentiment. But the economic dimension to the project has struggled to assert itself in a world in which size-matters. The government’s much vaunted post-Brexit trade deals are (according to its own projections) set to have a marginal impact on growth. In contrast, the longer-term negative impact of Brexit on UK growth and productivity has been put at 4%.

The UK has also signalled very openly that it intends to use every opportunity to seek a competitive advantage over the EU through the Brexit process. Yet, this ‘hidden in plain sight’ brazenness confronts the difficulty that the UK still needs to export to its largest trading partner (the EU) on favourable terms, giving the EU a lot of leverage.

This will be hard because – as I said in part 1 – the EU is in self-assertive mood. The UK-EU schism is not taking place in a vacuum, but in the context of an increasingly conflictual world order. The old free market globalisation is being displaced by ‘something else’, a more fractious system of competing regional economic and security blocs.

Brexit may be flawed in its design, but it has a certain logic in a world of rising fragmentation. It could be summarised: ‘in a more competitive world, don’t cooperate but fight hard to win’. Critics of Brexit will likely see in this everything they dislike about the project. But, we should also recognise, that this mentality is far from limited to the UK. Because it reflects structural conditions, we should not be surprised when we find examples of this hyper-competitive mindset among other actors.

So, is this happening on a wider scale? Does the Russian invasion of Ukraine push this tendency and dynamic further along? And does the EU offer an example of how this politics is playing out? Arguably, yes, yes and yes.

Towards a zero-sum world: preparing for a new era of geopolitical conflict

Growth of the type that generates rising living standards and relative stability may be coming to an end. We can already see how, since the 2008 financial crisis, a weak and uneven global recovery has fed into rising conflicts. This does not mean they are economically determined, but simply that struggles over how wealth is distributed (and also, how it is perceived to be) shapes many of the arguments and tensions that we see today.

In his recent blog post, James Meadway argues that the low growth problem is indicative of a capitalism running up against ecological and social limits. Long-term growth amenable to rising living standards usually involves productivity increases and 3% compound growth year-on-year. This is increasingly hard to come by in the ‘new normal’. The US only averaged 2.3% per year between 2009 and 2019, and even the once booming China is facing serious difficulties.

Looking at phases of growth supporting rising living standards, Meadway identifies three key ingredients: “a stable natural environment, cheap material inputs, and growth-biased technological innovations”. For our purposes, we will assume for the sake of argument that each of these three conditions no longer exists (for a longer analysis of why that might be the case I refer readers to the original piece) and we are moving into what Meadway calls a ‘zero-sum world’. This means economic benefits for one actor are achieved at the expense of another; and can be contrasted to a ‘positive sum world’ in which it is, in principle, possible for all to share in growing prosperity.

There are three different levels we might think about the ensuing competition for wealth and resources:

- Capital and labour. Following Thomas Piketty, Meadway notes how low growth, low productivity environments tend to advantage holders of capital over those selling their labour, producing rising inequality.

- Nation-states and regional blocs. States, and their various intergovernmental alliances, engage in heightened geopolitical competition in order to capture the growth that exists.

- Different geographical regions within the same state. While fiscal spending decisions by government may intensify inequality between regions, this problem will also express whether holders of capital (which – see point 1 – tend to benefit from these low-growth dynamics) concentrate in a particular area, like London.

The last decade has shown the complex ways in which conflicts over distribution are evolving. For instance, in relation to (3) we have witnessed tensions between ‘left behind’ geographies and capital-rich ones, even if they have not been expressed as conflicts over distribution but take the form of so-called ‘culture wars’.

So, how should we expect states and political leaders to behave in a situation of low growth?

I’ve talked about (incl in part 1) the rise of ‘them and us’ politics through the concept of authoritarian protectionism. This sees communities defined in ethnic terms by political leaders that claim to protect the nation from a series of threats ranged against them. Whereas Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan both argued that resources should flow to individuals on the basis of how hard they work (note that this does not mean their policies delivered this), in the authoritarian protectionist era these arguments are discarded, or at least de-prioritised. Instead, the ‘real people, the ordinary people, the decent people’ are held to have rights to resources simply on the basis of their identity.

The dangerous allure of ‘Europe first’

So, it is not hard to see how this combination of economic and ideological factors is contributing to instability in world politics. In short, we might say, ‘zero-sum conditions plus authoritarian protectionist reasoning equals geopolitical conflict’, as states seek to secure resources and growth at the expense of others. While as the author of this argument, I am not likely to disagree with it, there is clearly a danger insofar as it makes the counter-calculation look easy for liberals on the left: ‘just avoid nativist discourses, do some redistribution and carry on as you are’. Given the pressures of electoral politics we could easily drift into redistributing at the capital-labour level at home, while supporting the aggressive capture of value overseas through the use of coercive or semi-coercive measures.

Compared to ten years ago the left, especially those who are in government, are pretty content with the EU. Through the Next Generation EU programme, the bloc is now a source of vitally needed investment funds for its member-states, not a driver of austerity. Today’s EU also shows a preference for supporting state intervention and industrial strategy, de-prioritising many of the old shibboleths on state aid. But these should not be the only considerations for how we appraise EU policies. We have to look not only at the consequences of the framework for Europeans, but also, following (2) above, how it conceives of the allocation of resources in the wider world.

The recent Versailles Declaration is worrying on this score. It looks like a move in the direction of a ‘Europe first’ posture that resolutely prioritises the economic and security concerns of EU members. It sets the goals of reducing the EU’s ‘external dependencies’ (especially on Russia and China) in areas such as energy, critical raw materials, food supply, and semiconductors, and commits member states to substantially increase defence spending.

In its design this correlates closely – and tellingly – with Meadway’s prescriptions (excluding, of course, environmental stability) for economic growth that can deliver rising living standards. But in the absence of sustained growth, they are also particularly attuned to a low growth context due to their implied recognition that ‘cheap material inputs’ cannot be taken for granted. In light of greater geopolitical competition between powers, they seek to use the size and power of the EU to leverage more control of supply chains and critical raw materials.

The case study of critical raw materials

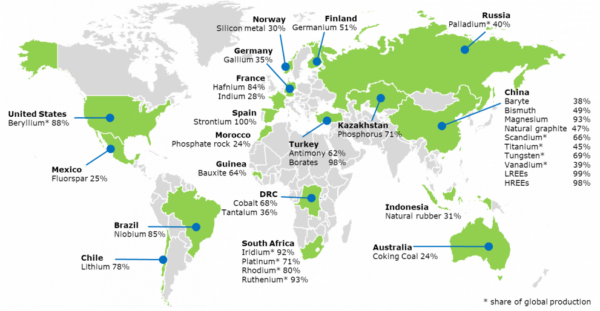

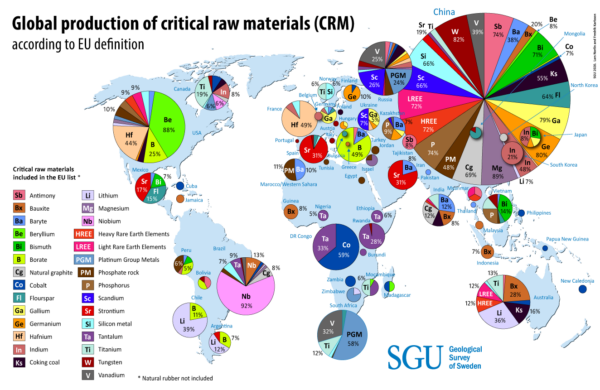

Despite the EU’s size there is no guarantee that this will be a success story. Take the example of critical raw materials, which are defined by the EU as “raw materials of high importance to the EU economy and of high risk associated with their supply”. In Map 1 we see the current EU critical raw material dependencies (including, notably, on China). In Map 2, we see available production and how this also provides a clear starting advantage to China.

In this situation, European states are presented with two choices: investigate potential for domestic resources and navigate the political opposition to mining them; or, look elsewhere for cheap sources of materials. And this, of course, sets the stage for a potential conflict between a ‘Europe first’ minded EU and low- and middle-income countries that possess critical raw materials. As Antonio M.A. Pedro, the director of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) Sub-regional Office for Central Africa, has argued, there is clear potential for conflict due to the irreconcilability of interests between a wealthy Europe that wants to stay that way and Africa:

“Africa needs to make the most of its strategic position as a major producer of some of the so-called battery minerals that are critical for the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. For example, 70% of global cobalt production comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and 80% of manganese resources are in South Africa. Gabon is also a major producer of manganese. Mozambique and Tanzania have significant reserves of graphite, and the DRC and Zambia are important sources of copper. But if nothing changes, the continent will continue to be locked in the lower end of these rapidly growing global value chains despite its significant mineral resources. So that’s one challenge. The second is how to manage the tensions between the developed world and Africa around the quest to secure access to critical resources for a green world, including those I have enumerated above. For instance, the European Green Deal aims to make Europe climate neutral by 2050 through, among other measures, an accelerated transition to clean energy, and the EU Critical Raw Materials Resilience pathway (COM [2020] 474) is focused on securing access to the raw materials that are critical for these transitions. And then you have the African Union with its Africa Mining Vision (AMV), which seeks to promote more local processing, value addition, and resource-driven industrialization, which could restrict the export of raw materials.”

These are, on the face of it, very difficult agendas and interests to bring together.

The Versailles Declaration: the new politics of ‘Europe first’?

On a very generous interpretation, the Versailles Declaration could offer a progressive approach to these issues. Supply chain security could be achieved through more infrastructure and aid investment overseas, combined with support for democracy and rule of law reform where necessary. Re-shoring of production in Europe could go alongside encouraging local approaches elsewhere in order to build more resilient, socially just and ecologically sustainable industries. The dangers of militarisation – including wasting precious resources, which could be put into green transition, on the military industrial complex – could be avoided by focusing on civilian responses to conflict, genuinely defensive armaments and prioritising collective security over deterrence, e.g., by emphasising arms control, multilateral frameworks based on human rights, and accountability through international criminal law.

However, it would take an inventive imagination to read the Declaration in these terms.

A less positive analysis point to a new ‘Europe first’ politics. This scenario would see spending flow to the military industrial complex, sucking resources from green investments. The focus on the principle of deterrence and militarism would bring with it more instability. The drive of greater power blocs to control supply chains and raw materials leads to extractivism with negative implications for the countries and peoples in which these production chains are rooted. Meanwhile, the old ‘fortress Europe’ tendencies in migration find more justification by a narrative that focuses on prioritising the interests of Europeans over non-Europeans and the human collective as a whole.

So, it is sadly not difficult to see the outlines of a ‘authoritarian protectionist’ EU in a liberal guise emerging from the turmoil of Putin’s war. But it is not, of course, inevitable. Citizens conscious of this danger can resist it by organising across borders around ecological and democratic alternatives based on the starting point of our common humanity.

Luke Cooper is a Senior Research Fellow at IDEAS, the foreign policy think tank of the London School of Economics. His book, Authoritarian Contagion; the Global Threat to Democracy (Bristol University Press), is out now.

March 16, 2022

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.