Measuring the Brexit impact on the economy: the evidence that points to a self-inflicted calamity

The UK economy is heading into a prolonged recession.

After Kwasi Kwarteng’s disastrous experiment in hyper-neoliberalism, his successor Jeremy Hunt has returned to the straight jacket of fiscal orthodoxy and relative moderation.

Last week’s statement aimed at repairing the capital markets’ confidence in the Government’s handling of the public finances in the shadow of the fall of the Truss government. Unlike Kwarteng, who had refused to publish an Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast when they announced huge unfunded tax cuts for the rich, the new regime has returned to the norms of fiscal oversight and scrutiny.

The new OBR report makes interesting reading – especially in terms of what the authors say about the impact of Brexit. Drawing on the available evidence, they argue:

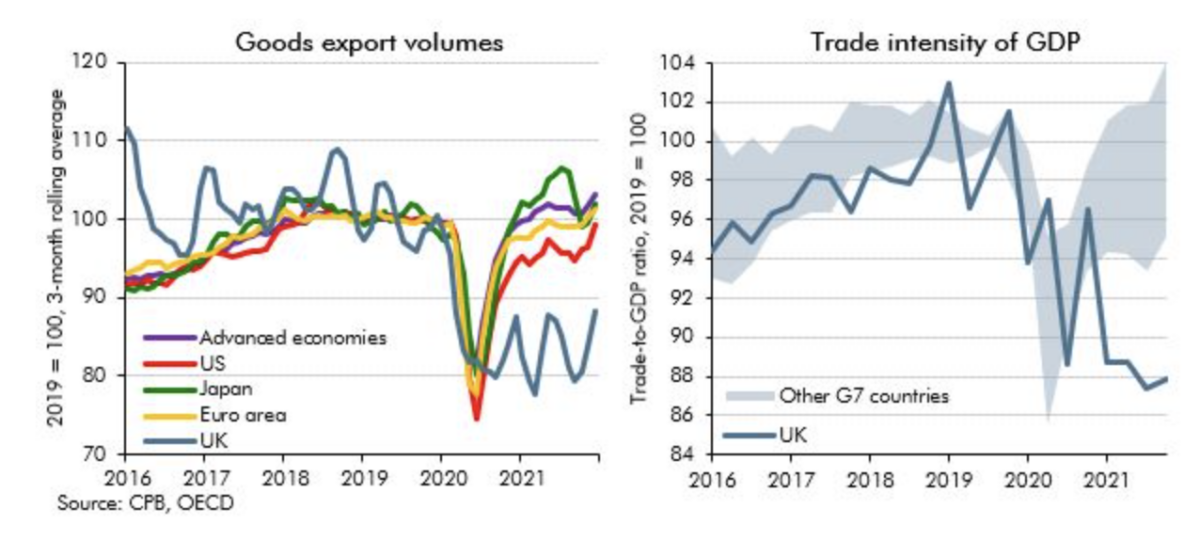

Near-term growth in exports and imports is lower than in our March forecast as slowing global GDP growth hits exports and a weaker outlook for consumption and investment weighs on imports. Our trade forecast reflects our assumption that Brexit will result in the UK’s trade intensity being 15 per cent lower in the long run than if the UK had remained in the EU. The latest evidence suggests that Brexit has had a significant adverse impact on UK trade, via reducing both overall trade volumes and the number of trading relationships between UK and EU firms.

As the UK ended the ‘transitional period’ nearly two years ago, we now have ample data on the impact that they describe. In contrast to other G7 economies, the UK’s trade volumes and exports have failed to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic:

Even prior to its formal exit from the EU, the UK had already taken a hit from the anticipation of negative economic affects from Brexit. Since 2016, business investment has been stagnant – and it has not improved since the government introduced generous investment allowances (which provide companies with tax relief). In this chart from the Financial Times the light blue line is the 2009 to 2016 trend level, the dark blue line is the actual level of business investment and the ‘superdeduction’ shows when the tax breaks were introduced.

It paints a bleak picture for the post-Brexit health of the UK economy:

Many countries globally are now grappling with the problem of high inflation. But this has proven to be a more serious problem in the UK than other equivalent economies. The OBR report says:

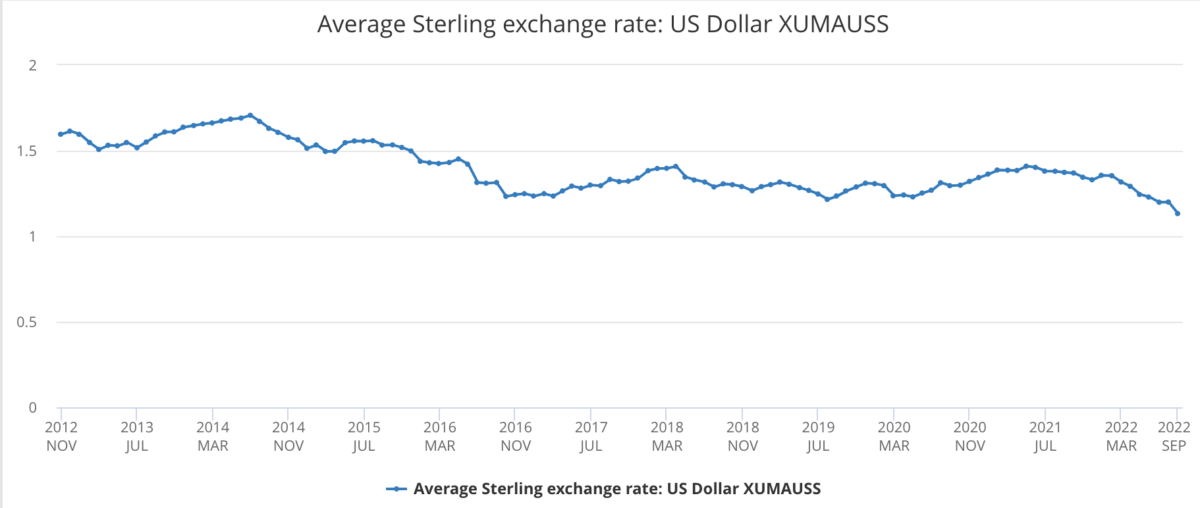

Food and non-alcoholic beverage prices rose 14.5 per cent in the year to September 2022, the highest rate in more than 40 years, and we expect high food price inflation to continue in the near term. Food, beverages, and tobacco are expected to contribute 1.5 percentage points to inflation in 2023 as a whole. The weaker pound also raises food prices as the UK imports around half of its food.

Since 2016, the weakening of confidence in the UK economy has led to downward pressure on the pound – a process that reached its epitome under the calamitous Truss government. Whereas in July 2015, £1 would get you more than $1.5 dollars after 2016 it has oscillated at just above parity:

Since the end of the transitional period, the UK has also introduced new barriers to trade with our biggest trading partner, the EU, raising the costs of imports. As the UK does not have sufficient capacity to make up for more costly imports by producing more domestically, the end result is higher levels of inflation for UK consumers.

Now, the OECD has also joined the OBR in making an entirely negative analysis of the UK economy. In their new report, they anticipate that over the next two years only Russia will have a worse level of economic performance than the UK in the entire G20. They also point out that the UK is the only economy in the G7 where output has not returned to pre-pandemic levels. Facing a prolonged recession, this negative UK picture is set to get even worse.

It is little wonder then that the Conservatives are under acute pressure to revise their trading arrangements with the EU in order to re-open access the European single market. But it seems likely that – at least for the time being – Brexit ideology will not allow any serious recognition of the economic reality.

November 22, 2022

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.