Jonathan Hopkin on Britain after Brexit: a low immigration, high wage economy?

Jonathan Hopkin is Professor of Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics. In this guest blog for Brexit Spotlight, he looks at country-by-country data to illustrate the profound implausibility of Boris Johnson’s claim that leaving the European Union and ending free movement will deliver a ‘high wage, high productivity economy’.

The new barriers to trade and migration arising from the ‘hard Brexit’ negotiated by Boris Johnson’s Conservative government were long predicted by many to result in higher prices, shortages and delays for British consumers. Such warnings were dismissed as ‘Project Fear’ by Brexit supporters in 2016, but with empty shelves in supermarkets and long queues for petrol across the country, the government’s story has changed.

On the eve of the 2021 Conservative party conference, the Prime Minister celebrated these disruptions as the growing pains of a new, and better economic model: “When people voted for change in 2016 & when people voted for change in 2019, they voted for the end of a broken model of the UK economy that relied on low wages & low skills and chronic low productivity. We’re moving away from that.”

The implication of this statement is that EU membership was the cause of Britain’s low wage low productivity equilibrium, particularly because of the easy availability of low paid migrant labour from Eastern and Southern Europe facilitated by EU freedom of movement. New migration rules curtailing migration will therefore, according to the PM, break with Britain’s longstanding dependence on low skilled EU labour and force employers to train and reward British workers, bringing higher productivity and higher wages, especially for working class voters in ‘Red Wall’ constituencies.

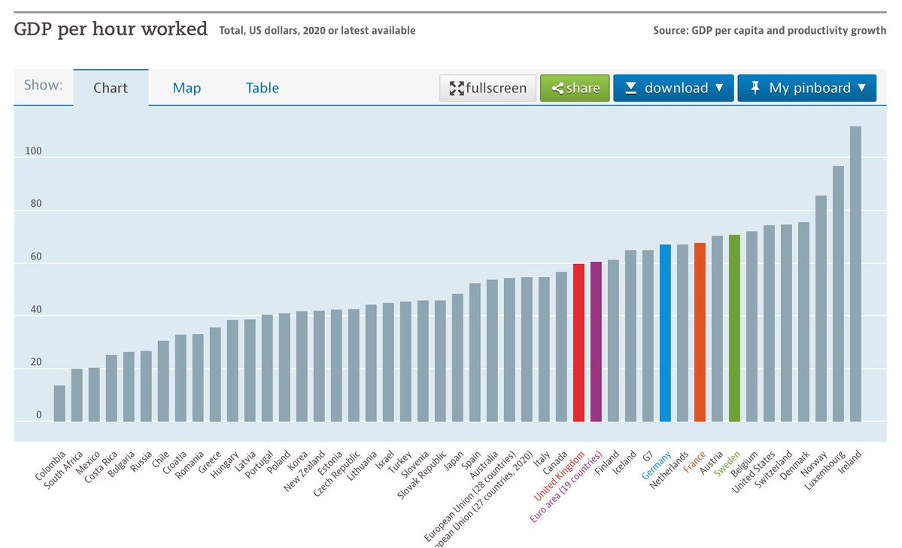

The trouble with this argument is that it simply does not match the international evidence on productivity and wages. Data from the OECD (Figure 1) tells us that apart from the US, all the OECD economies with higher productivity than Britain are actually in the EU (or, like Switzerland, Iceland and Norway, have deep trade agreements with it). Sweden, Germany and France, all EU countries with freedom of movement of EU labour, have higher productivity than the UK. How can EU membership be a reason for Britain’s historically poor productivity performance when the EU members most similar to Britain do better?

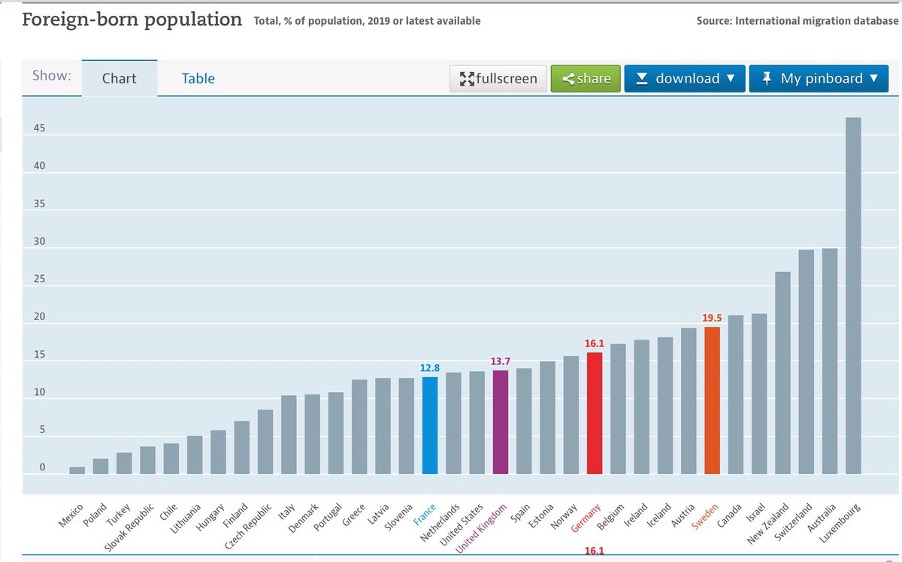

One argument frequently wheeled out to explain this contradiction is that Britain, alone amongst the mature industrial economies of the EU, chose to embrace the 2004 Eastern enlargement by welcoming workers from the new member states immediately, rather than imposing a transition period like other Northern European countries. But despite this liberal approach Britain has not had higher migration than other European countries. Sweden and Germany still have a higher foreign-born population than the UK, without this having apparently affected their productivity (see Figure 2).

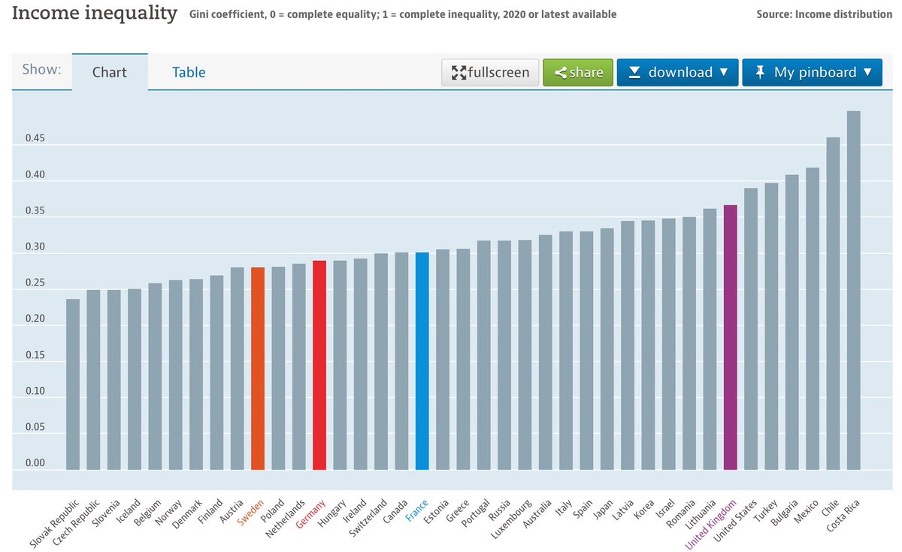

Aside from productivity, Brexit supporters often claim that the EU and its free movement of labour system was responsible for driving down the wages of lower-skilled British workers, by subjecting them to brutal competition from Eastern Europeans happy to work harder for less. Yet, other EU countries did not seem to have this problem. OECD data in Figure 3 shows that income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, is higher in Britain than in any EU country apart from Bulgaria.

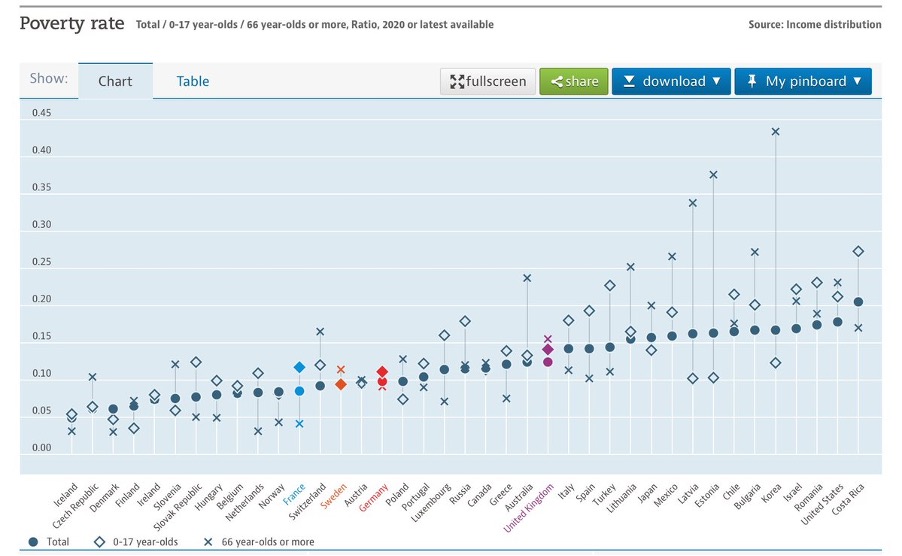

Figure 4 shows that poverty is also above the European average, whilst Figure 5 reveals that the share of Britons on low wages is higher than any other pre-2004 EU country. Can the EU really be responsible for how Britain treats its poor when almost every other comparable member state does better?

In sum, if most EU countries have better productivity, higher wages and lower inequality than the UK, it makes no sense at all to believe that being in the EU reduces wages or productivity. Leaving the EU, on its own, will therefore do nothing to solve the problem. The policies needed were available to us inside the EU, they do not magically come about just because we left.

Britain’s productivity and poverty problems cannot be blamed on the EU, but on the peculiar economic model that our own governments have chosen over the past decades: a model in which businesses invest as little as they can get away with, and employees are a commodity to be hired and fired at will, with few companies having the resources or the longsightedness to invest in the tools and skills needed to be more productive.

There is an alternative. It’s just not what the government are offering

The more advanced EU members do not operate like this. Businesses build cooperative relationships with workers through well organised trade unions, backed up by legislation and a supportive political environment. This enables companies to take the long view and train their workforces, whilst workers have greater job security and social benefits, allowing them to take the risk of acquiring specific skills that may tie them to a particular sector. In countries like Sweden, Germany or France, companies do not rely on ‘mainlining’ cheap Eastern European labour, and few businesses take seriously the prospect of leaving the European Single Market.

Unfortunately, the current Conservative government shows no signs at all of having understood why Britain has lower wages and productivity. And that’s to be charitable. There are many reasons for thinking they are actively opposed to the kinds of policies that would improve things, preferring to rely on speculative financial inflows and a hyper-inflated housing market to drive the economy. Brexit is likely to act as a drag on productivity growth and living standards unless the current hazy mix of aggressive nationalism and free market fanaticism is replaced by something smarter.

October 6, 2021

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.