Do voters really want to reverse Brexit?

Many do but we should look beyond the clickbait headlines.

The recent Savanta ComRes polling sparked a flurry of online shares. Always quick to identify an opportunity for ‘clickbait’, the Independent and the Express ran stories declaring, in the latter’s words, “Boris dealt huge blow as more than HALF of UK adults want to REJOIN EU”.

There are certainly positives in the polling for critics of Brexit. But the data also shows emphatically that the country is still very divided – and there is no major collapse in support for staying out of the EU from Brexit voters.

The poll show surprising levels of support for a re-join referendum

On the critical issue of whether to hold the referendum which would be necessary for the UK to re-join the EU, voters are pretty split with 40% supporting and 34% opposing:

Strongly support 23%

Somewhat support 17%

NET SUPPORT 40%

Somewhat oppose 8%

Strongly oppose 26%

NET OPPOSE 34%

Neither support nor oppose 19%

Don’t know 7%

Now, this data is encouraging for pro-Europeans. It shows surprisingly high levels of support for holding a referendum within the next five years and lower levels of outright opposition than we might have feared.

Looking closely at the raw data, we can see that a significant chunk (21%) of 2019 Conservative voters would support holding a referendum on re-joining and another 11% neither supports nor opposes the policy. While 54% of these voters ‘strongly oppose’ holding a new vote, and another 10% ‘somewhat oppose’ doing so, this is not the level of resistance that we might reasonably expect given the party’s 2017 and 2019 election campaigns have been so trenchantly pro-leaving the EU and categorically against a referendum in any circumstances.

The level of public support for a referendum within the next five years is also surprising given the total absence of the argument in favour of one within the UK political debate. Not only has no major UK political party adopted this policy, but even amongst ‘post-Remain’ groups there is scarcely any active campaigning for a new referendum.

The country is still divided in two

Still, for the most part, this is a story about the relative solidity of pro-EU support and the potential fragility of the Leave vote. It does not show vast numbers of people switching from Leave to Remain. The Savanta ComRes finding that sparked the clickbait headlines showed that 53% supported re-join while 47% backed staying out. This is very consistent with long-standing polling trends that show an oscillation around the 50/50 mark for the two sides.

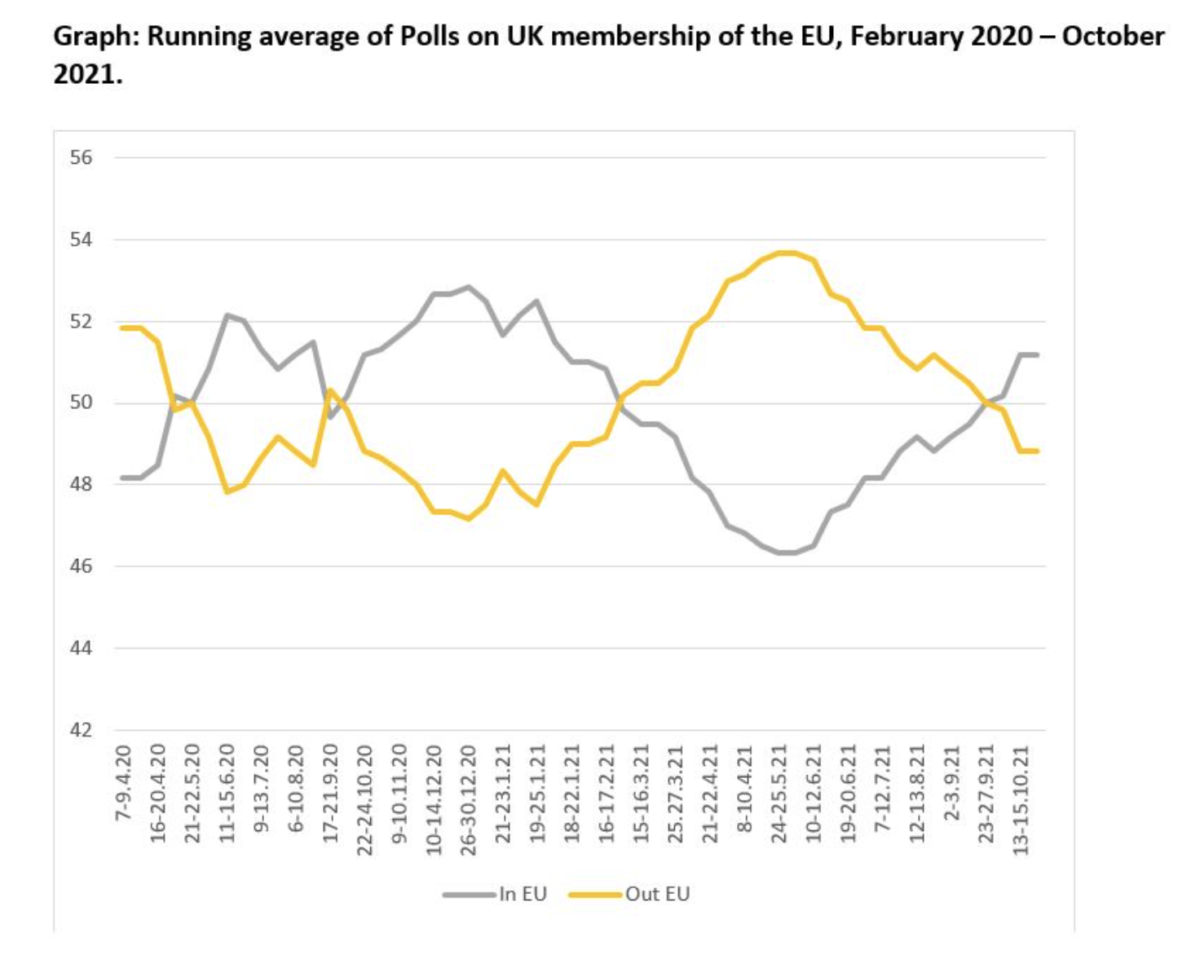

The pollster John Curtice recently aggregated data from February 2020 to October 2021 (see Graph 1). Notably, he found that “[n]ever has the average level of support for being out of the EU been less than 47% or more than 54%”, i.e., the UK is still split down the middle. In the same blog, Curtice highlighted how this tracks very similar trends in the post-2016 polling, which has tended to see both sides with about 50/50 levels of support. However, interestingly, remain/re-join has had a consistent lead amongst those that didn’t vote in the 2016 referendum – with, on average, just 15% saying they would vote to stay out and 35% arguing that they would vote to re-join.

Furthermore, as Curtice notes, this helps explain why support for remain/re-join has been strong, despite slightly fewer Remainers sticking with their 2016 vote (75%), i.e., not changing their minds, than Leavers (79%). So, once you add in demographic change (i.e., new, younger pro-EU voters turning 18, and older, more Leave-inclined voters passing away), this could be expected to give re-join a strategic long-term advantage over ‘stay out’.

The rub of the problem: a narrow ‘re-join’ lead is not enough

Nonetheless, ultimately, re-join has the problem that a narrow polling lead is not enough. While formally any majority to go back in would be sufficient in a referendum, this cannot be made to fit the reality, either in terms of getting the referendum in the first place, or the complications a narrow vote would pose for a new UK membership application.

In domestic politics, re-join would need to be enjoying thumping polling majorities in order for politicians to countenance swinging behind a new referendum. With the partial exceptions of the Greens and SNP, all the other parties – including even the Liberal Democrats in their west country targets – need the support of both stay-outers and re-joiners to gain seats. So, more movement in public opinion would be required than we’ve seen so far.

But, more importantly, at the EU level, there will be little appetite to re-visit the question of the UK’s membership unless there is a sustainable, i.e., numerically significant, majority in UK public opinion for going back in – and, even then, support is far from assured, not least because it would require unanimous support from all EU member states.

Of course, it is not hard to imagine a situation that would create conditions for UK membership becoming viable from an EU perspective. A new government is elected, which negotiates a single-market-like arrangement, enjoys domestic support for this approach and oversees a consequent ‘thawing’ and stabilisation of relations with the EU.

We are still some way off from this scenario. But we should, of course, prepare for it.

November 16, 2021

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.